By Jeffrey A. Rendall

Photos by Jeffrey A. Rendall and ReesJones.com

Rees Jones knows golf, and he knows life. The son of legendary course architect Robert Trent Jones, Rees studied at Yale and Harvard prior to joining his dad's firm in 1965. In 1974, he established Rees Jones Inc, which he now operates out of his hometown of Montclair, New Jersey.

There's quite a lot of talk in golf circles about architecture, specifically speaking about styles, philosophies and traditions. A lot of those conversations involve Jones, whose work spans decades and geographic regions. And because he's been around golf course construction his entire life, he's developed a unique perspective on old-style methods as well as the latest in technological advancements.

But the philosophies are still the same. Mike Mayer, the Director of Golf at Wintergreen Resort (where Jones designed 27 holes), told me "If you're standing on the first tee, and you can't see precisely the shot you'll need to hit, then you're not on a Rees Jones designed golf course." That's true. Jones' work may not wow you with the flash and flare of some other designers, but if you're looking for fair, aesthetically pleasing tests of the game, then he's the man.

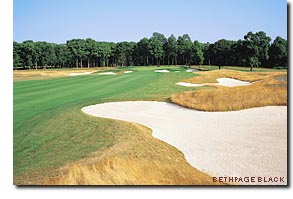

It's because of those philosophies that Jones is often called in to consult on golf's premier layouts. His resume includes the design or redesign of over 100 courses, including this year's US Open venue (Bethpage Black in New York) and PGA Championship venue (Hazeltine National Golf Club in Minnesota). Jones' reputation as a re-maker of championship layouts has led to the nickname "The Open Doctor," and he's often seen on the Golf Channel whenever a major championship's in the works (or at least it seems that way).

I've had the opportunity to speak with Rees on several occasions, and he's generously lent his considerable knowledge and experience to course reviews in the region. Here are some excerpts from several different interviews, where Rees talks on everything from growing up in his father's business, to the relative importance of walking courses, to what he hopes players take from the game:

|

| The Golden Horseshoe Green Course's par five 5th hole. |

Q: I read an article a while back that compared yours and your father's styles and philosophies. I found it really interesting that you've been around golf courses your whole life. I'd imagine after a while, designing comes pretty naturally to you?

Rees: Yes it does. Plus, when you grow up in it, as I did, and sort of learn from your father's footsteps -- when you're a baby sort of crawling around on the floor, he picks you up and he teaches you. Just by being around him, I learned a lot about the game.

It's funny -- I recently did a video about how to play a course's design, and how it's important to not just get instruction on how to hit the ball, but rather to learn about how to read a golf course and play within your limitations. The strategy of the game is so important, and I think that's what we do in our designs -- we really work very hard on the strategy to give people alternate shot approaches. And playing the angles, making sure they benefit from playing the proper side of the fairway.

Q: Do you think it's ever possible to properly play a golf course the first time?

Rees: Not unless you have a caddy. If you don't have a caddy, I think you're just learning your first time out.

When you go over to the British Isles, you have caddies. You couldn't play those golf courses without caddies. Yardage books give you distances and hazard placements, but caddies help you play the wind. Caddies are coming back now at a lot of clubs, so it's not like they're a dying breed. So I think you can play a golf course with a caddy and learn much more about it from those who took a lot of people around it before you.

|

| One of the Green Course's terrific par threes, the 188 yard 7th. |

I once hosted one of my project managers from down in Hilton Head. Brought him up here and we played with a caddy. And it was the greatest experience for him -- and he played better than he ever played before. He'd never walked a course with a caddy and then he played better than he ever had before.

Q: Is it important, from a design standpoint, to design a course that's walkable?

Rees: No. Well, it really depends. I think walking is over emphasized. Because today we have wetlands and terrain that -- you know, in the old days, they built courses on much smaller pieces of property, and didn't have any environmental restrictions, so they had the greens and tees very close to one another.

Now, I think the important thing is to make sure that all 18 holes are as good as they can be. And if it means walking farther from greens to the next tee to get to another hole, that's really the objective. And, when they talk about walking and walkability in golf publications, well, I don't think you should be in any hurry to finish a round of golf.

Stanley Thompson, the architect who really taught my father, used to say -- having long distances between greens and tees is very beneficial because you can regroup, rather than just getting up to the next hole and hitting away. You have time to think about the next shot, and you can play the game a little bit better.

So I think we should try and make them easier to walk, yes, but also make sure we're using the land to the optimum. If it means walking a little bit longer distances from green to tee, then so be it, because they're better holes.

|

| Early morning light and shadow reveals Jones' eye for contour. Here, the Green Course par 4 4th hole |

Q: Do you see golf carts as, say, a bad part of the game?

Rees: No. I think they're -- especially when you're down in the heat of the South -- they're very essential.

That being said, I think that, when you walk a course, as my friend Jack Best did, he played better because he didn't rush to the next ball, and he paced himself. You pace yourself when you walk, and you actually start feeling the hole.

When you ride in a cart, quite often you have the cart path, and you come in and you're not on that hole. You have to 'feel' the hole in order to play a complete round of golf and I think walking -- whether it's carrying your own bag or pulling a trolley or having a caddy, really gives you a better opportunity to enjoy the visual landscape -- because I call a golf course a nature walk to play on. You're really walking in many native areas.

And to drive around it and speed drive and not even see where you're going... golf is an escape. It's getting away from the travails of life, and if you concentrate hard enough, you will, even mentally, get away from all your worries. But if you're in a hurry, and you've got range finders on, and you've got your cell phone with you... it's not really what golf's supposed to be. Golf's supposed to be a form of relaxation.

Q: I've noticed on several of your courses that you'll put mounding on the sides of the fairways. What's you're thinking behind that?

|

| Jones deepened the bunkers on his father's Golden Horseshoe Gold Course. Here, it's the par 4 13th hole. |

Rees: I've used mounding on places like the Green Course at the Golden Horseshoe to try and keep the golf balls from going down the ravines. But now, with these drivers they have, mounds won't even stop that anymore.

In the Green Course's example, I was trying to make it user friendly -- wider than my Dad's course (Gold Course), and one thing we did when we redid the Gold Course was to regrade the fairways so the ball would kick back towards the center. For holes like 8 and 9, if you went right, you really went down. So that's what we were trying to do with the Green Course -- the mounding sort of keeps you in play.

Q: There's a lot of talk these days about gimmicks in golf course design. But, if there's a defining characteristic in your work, it's that you can see your targets. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Rees: Basically, I think, as a designer, you've got to design a course (especially in a resort context) that's dramatic looking, but where the player can still shoot what he's trying to shoot -- trying to break 90 or 80, and that there's a chance the course will allow him to do that. You don't want him standing on the first tee thinking he's got no chance to shoot that score.

Some of the newer courses are grand visual experiences, but they're so difficult that you'll have no possibility of achieving what you set out to do.

|

| The cartpath suggests the shot on the Gold Course's par four 17th....long and straight. |

Q: Now, what types of design features would you put into a resort style course that would make it, say, a little bit more player friendly?

Rees: Well, I think you'll put in a wider target, and I think that's what we tried to do with the Green course. And create green contours that have a lot of transitions in them, but at least in areas where you'd put the cup, it's not too severe. I think you really want to have definition so the golfer can see the target both off the tee and into the green. If they can visualize the shot, there's a really good chance they'll be able to perform it. If there are blind shots on a resort course, they really can't visualize it and they're just hitting away and they can't concentrate. So I think definition is very important on resort courses.

You've also got to make sure the greens are receptive for the length of the shot.

Q: In your mind, what makes for a successful golf course?

Rees: The real measure of a successful golf course is whether people will want to come back to play it again. A lot of courses may be visually dramatic, but they'll play so difficult that people are exhausted by the time they're done.

Golf courses have to be designed to be of continuing interest. We're not trying to design the ultimate examination every time, because only a few people can play those golf courses -- and those golfers certainly don't pay for their rounds.

|

| Looking back up towards the tee from the Gold Course's 16th hole, the first of the Course's island greens. |

Let's also remember that golf is supposed to be relaxing. Most people aren't having much fun when they're in trouble all the time on a golf course, and they'll hesitate to return if a course is excessively difficult or unfair.

Q: In recent months, I've attended some grand openings where Pete Dye, Arnold Palmer and Tom Clark touched on the new equipment and new golf balls, and how they're now having to build longer and longer courses to keep up. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Rees: Well, you know at Wimbledon they play the tournament with the same tennis ball. So I think maybe there should be a tournament spec ball. But I don't think they ought to reign the equipment in. And with some of the equipment that people have now, it'd be hard to do. The real problem is some of the older golf courses really are defenseless unless they have the green contours, bunkering and hard pins to access.

We worked on Torrey Pines out in San Diego, and that course can stretch out to 7600 yards now, though for this year's tournament they didn't even use all the length. But you can make a course challenging in other ways, too.

Q: Well obviously you worked on Bethpage and were able to make it enough of a test for all of these professional long hitters.

Rees: Well, I think Bethpage, because of the bunkering and the location of the bunkers, had enough distance to challenge the pros. And the green contours are kind of subtle, so they were treacherous when run at high speeds. They didn't have to worry about the greens not having enough pitch, when they ran 'em at high speeds.

|

And the layout is phenomenal, it's got a lot of long par fours. You know, that's what really challenged 'em at Congressional, and that's what challenged 'em at Brookline. And, one thing about the Open and the PGA, is they tighten up the landing areas -- so hitting into the rough is definitely a penalty. The players had to make a choice on whether to hit driver or not, so they couldn't always take advantage of the increased length the equipment provides. They have to think their way around an Open.

In the Mid-Atlantic region, Jones has left his mark on several noteworthy layouts, such as the Green and Gold Courses at the Golden Horseshoe (the Gold Course was a redesign of his father's from the early sixties), Hell's Point, Greenbrier Golf Club (in Chesapeake), Stoney Creek at Wintergreen and a redesign of Congressional Country Club's Blue Course, which hosted the 1997 US Open.

Thinking is a big part of what Rees Jones asks of you when you play one of his layouts. And it's not just about golf - he wants you to enjoy the entire experience. To him, playing the game has a higher purpose.

Details:

For more information on Rees Jones, please see www.reesjones.com.

| Related Links | Comments on this article? | |

|

Maryland National Golf Club Hollow Creek Golf Club Rocky Gap Resort PB Dye Golf Club in Ijamsville Whiskey Creek Golf Club |

E-mail Jeff Rendall, Editor: jrendall@golftheunitedstates.com |